Notes

memory of a mother's love

This is an edited version of a blog post I wrote six years ago … my oldest was just starting 7th grade. This was before any of my children had cell phones.

I’m not really sure what I need to do, what to write, to get my daughter out of school today. I don’t address it to anyone, mostly because I don’t know to whom it’s going. Dear School? Dear Person in the Front Office? I forgo the greeting and write: Please excuse Nadia from school today at 1:20 p.m. She has a dentist appointment. Thank you.

I sign my name, then quickly add my phone number below, as if this brings some increased level of authenticity. My daughter is not the only one new to middle school in this family, she’s not the only one who feels self-conscious. The note is written on a small piece of paper torn from a hotel notepad, the kind I compulsively throw into my bag whenever we go away. Should it be on personalized stationery instead? Nice heavyweight paper?

While signing my name, it strikes me how I’ve been writing more and more notes lately.

We’re at a doctor’s appointment for Viv. Love, Mom

Nadia, I’m at the school volunteering, I’ll be home by 3:15. [Heart], Mom

Went for a quick walk, will be home soon. Love you, mom.

These are all to my oldest child, the one who gets home the earliest in the afternoons now. The one who strides with pre-adolescent confidence into the next phase of her life. The one who is not as physically attached to me as she once was.

The notes I write are not a big deal.

They’re not.

They’re just a simple way of staying connected in short-form. Of communicating where I am and the plan. Of letting her know she was on my mind, ever and always, and whether she cares or not, how she’s connected to me.

The notes are often written on throw-away pieces of paper: post-its, the backside of her younger brother’s math homework, a receipt from CVS. They’re nothing to keep. Nothing to hold onto.

Nothing.

Nothing.

Nothing.

When three of my four kids started school this past year, I gave myself a few big tasks to work through during my precious kid-free preschool hours each week. One goal was to organize the back room of our house. We call it the computer room, but a better name would be something like ‘room with all the things we don’t know what to do with’ or ‘young artist supply warehouse’ or ‘paper graveyard.’

I have piles — literal, stackable piles — of adoption paperwork I’ve had no bandwidth to sort through for the last two years. There are doubles of every authentication we had to complete, passport copies in triplicate, our travel itinerary quadrupled. There is a Melissa & Doug art easel that not one of the children has used in at least two years. A clear plastic bin in the corner is filled with anything that could be glued, sewn, painted, applied, bent, or bedazzled, labeled CRAFT CRAP.

One of the drawers in the desk is crammed so full of old bills and bank statements — who gets paper statements anymore? — mixed in with birthday cards, atop stacks of blank CDs/DVDs — again, what? — and boxes, yes, plural, boxes of checks from financial institutions with which we are no longer affiliated, I can hardly open it.

The kids have been in school for at least two months now and here I am, finally ready to tackle this space. But because I never know where to begin, I do what I always do: spend twenty-seven minutes finding the right playlist.

Next, I spin. In literal circles. Like a dog before laying down, looking for the best section in which to start.

I’m a person who gets stuck in potential. I adore optimizing, efficiency, and ease — mostly because it’s everything I’m not. And the idea of having a systematic and streamlined process makes me so hopeful. It’s just that I don’t have any of that. I don’t know where to begin.

Whether I’m cleaning out a back room, writing an essay, or writing a note to my daughter’s school, it’s always the same — lengthy procrastination followed by angst, followed by a search for a perfect playlist followed, finally, by action.

I decide to take the advice I’ve been giving myself lately, to just start anywhere. I’m a golden retriever getting ready to eat an elephant. Paper by paper, I create Kid/Keep piles, Trash piles, Shred piles. I start dreaming up systems and even as I work, create Big Plans to avoid another multi-year paperwork pileup.

No paper in the house! None. Just like that guy I read about who takes pictures of receipts and uses a pro version of Evernote. No mail allowed inside! Recycling bin is my best friend! I’ll be a savage with preschool art!

I curse the institutions who send me paper. I lament over the trees.

And then, hours in, with my back hurting, I sit on my rear end with my legs splayed out wide. I’ve finished sorting one of the biggest paper piles and I lean over, reaching for the container with the white lid I’d pulled out of the closet earlier.

It’s the one I’ve had since high school, the one I packed up and moved with when I got married. It’s full of totally unimportant papers, ones that carry only immeasurable emotional weight for me. Journals, notes, letters. My life before this one.

Move along, don’t open it now.

But I don’t move along. I, for whatever reason, refuse to move along.

Something in me deeply, deeply wants to see inside. To explore. To excavate.

And maybe this is another reason why I procrastinate so often with this room. Why it takes me months, if not years, to sit down with a task that shouldn’t take all that much time, but will, if I give myself over to such things as this.

Under the white lid is a stack of manilla folders with a newspaper clipping from 1983 on top. I was in Kindergarten. I am on the front page of our local paper, in a navy blue dress, pig tails and bangs, decorating a gingerbread man. (We lived in a very small town.) In the folders below that are stories I wrote in grade school, Valentine’s I’ve kept, report cards I don’t need to keep.

I pick up a smooth brown planner that lays in the middle of the bin. Move along, Sonya.

But I can’t.

I know exactly what it is, whose it is. I’m doing this to myself on purpose.

I open it to one of the first pages. It’s full of measurements, printed in Cyrillic script —the formal written Serbian language, my mother’s native tongue.

Put it back. You don’t have time for this.

But I keep flipping.

I don’t know what I’m looking for, only that I’m searching.

I’m always searching.

I flip through page after page of the planner, from the last year of her life. Most pages have little notes written in my mother’s classic Eastern European script. English words are misspelled everywhere. There are recipes, tallies of weekly spending, receipts from the local department store and the ATM. Sermon notes are written on the back of an upside-down envelope. In one section, she’d written short entries, almost like a journal. One makes me gasp.

It wasn’t like I went through the house scooping up physical memories of her after she died. She was still there, then. Still everywhere.

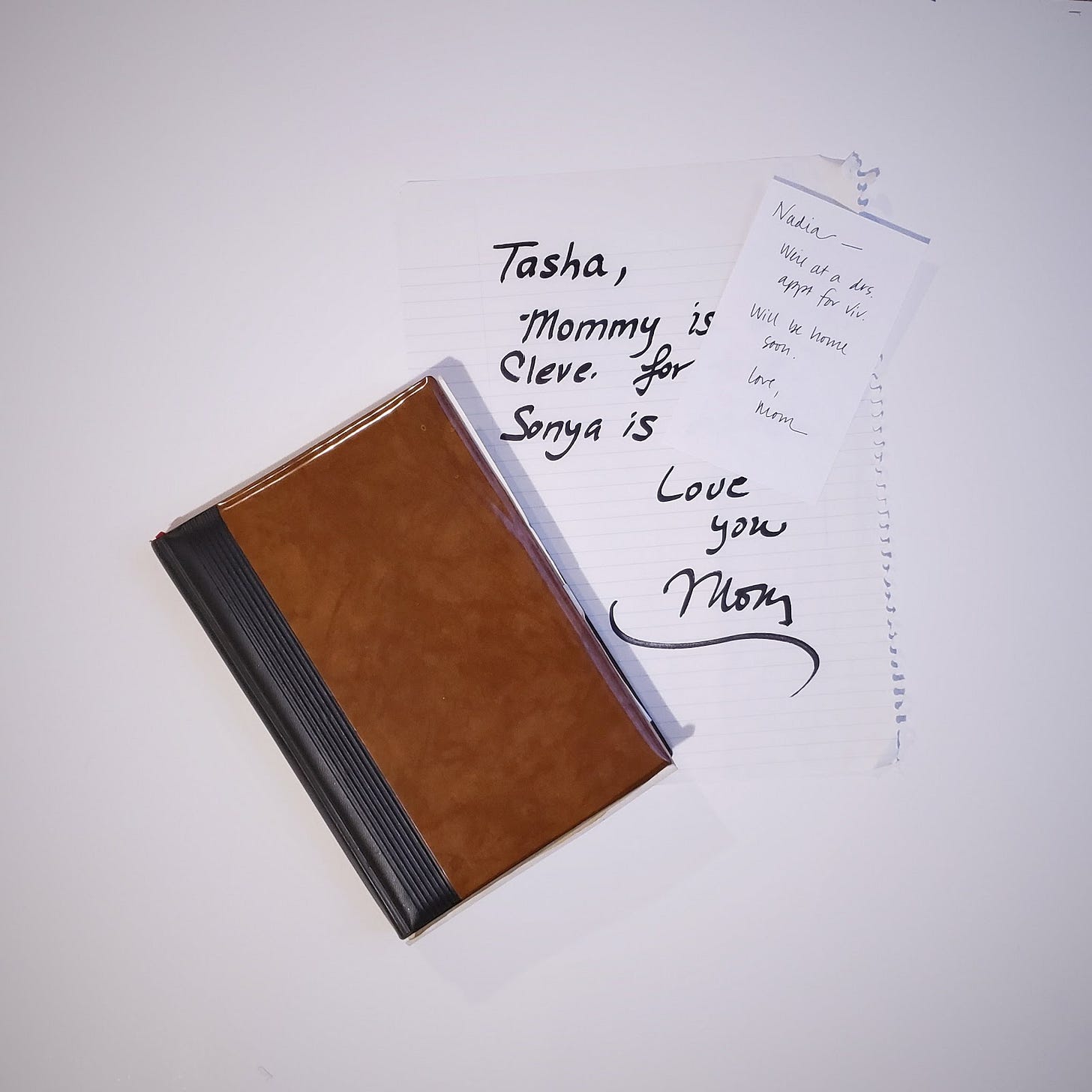

But at some point, I claimed this planner. Her recipe box. And kept a handful of random notes she wrote to me and my siblings.

With a deep breath, for I can only stand this feeling of wanting something I can’t have for so long, I close the planner and place it back in the container. I replace the lid and push it back into the closet. I stack my children’s memory boxes on top of mine.

Piles of paper sit all around me. Much of it is useless, unnecessary.

And yet I hold onto these scraps of my mother’s papers. Physical proof of her handwriting. Of her existence. Of a random day where she wanted to tell my little sister where she was and why.

Without expecting it, a wave of emotion rises up my neck, through the back of my throat, into my face. Tears tumble from my eyes.

It’s how she wrote my name.

It’s how she wrote my sister's name.

How she signed Mom.

How she wrote Love you

And how one day, the notes stopped. And we’d never get another.

The notes I write to my daughter might seem, might feel, might look inconsequential. I’m running to the grocery store. I’m at a doctor’s appointment. Picking up a book from the library, will be home soon. On the surface, they’re just practical. But for me, they carry so much weight. Because if you go just a little bit deeper — what you find is a mother’s love. love you.

And that’s everything.

so beautiful, sonya. thank you for sharing your words and your heart. 💕

read this with my heart in my belly. the longing and searching for the connections to her. and the parallels to the intentionality in how you're parenting. Love your deep soul.